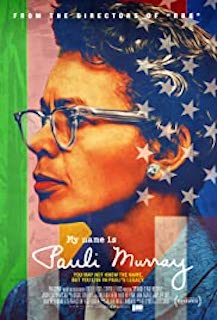

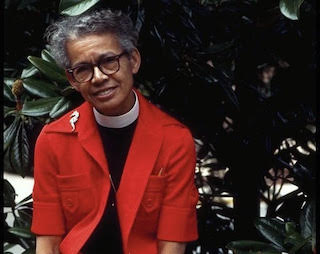

Claudia Raschke is an award-winning New York City based cinematographer best known for such films as Oscar-nominated and Emmy winning RBG (Magnolia/ Participant/ CNN), Oscar-nominated God is Bigger Than Elvis (HBO), Peabody Award-winning Black Magic (ESPN), Oscar short-listed Mad Hot Ballroom (Paramount), Particle Fever (Bond), Atomic Homefront (HBO), and The Freedom to Marry (Argot Pictures). Her latest film, which screened at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, is My Name is Pauli Murray. Fifteen years before Rosa Parks refused to surrender her bus seat, and a full decade before the U.S. Supreme Court overturned separate-but-equal legislation, Pauli Murray was already knee-deep fighting for social justice. A pioneering attorney, activist and dedicated memoirist, Murray shaped landmark litigation—and consciousness— around race and gender equity. As an African American youth raised in the segregated South—who was also wrestling with broader notions of gender identity—Murray understood, intrinsically, what it was to exist beyond previously accepted categories and cultural norms. The film was made by the same team that made RBG including directors Julie Cohen and Betsy West, producer Talleah Bridges McMahon and editor Cinque Northern. My conversation with Raschke, via email, began with that team.

Claudia Raschke is an award-winning New York City based cinematographer best known for such films as Oscar-nominated and Emmy winning RBG (Magnolia/ Participant/ CNN), Oscar-nominated God is Bigger Than Elvis (HBO), Peabody Award-winning Black Magic (ESPN), Oscar short-listed Mad Hot Ballroom (Paramount), Particle Fever (Bond), Atomic Homefront (HBO), and The Freedom to Marry (Argot Pictures). Her latest film, which screened at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, is My Name is Pauli Murray. Fifteen years before Rosa Parks refused to surrender her bus seat, and a full decade before the U.S. Supreme Court overturned separate-but-equal legislation, Pauli Murray was already knee-deep fighting for social justice. A pioneering attorney, activist and dedicated memoirist, Murray shaped landmark litigation—and consciousness— around race and gender equity. As an African American youth raised in the segregated South—who was also wrestling with broader notions of gender identity—Murray understood, intrinsically, what it was to exist beyond previously accepted categories and cultural norms. The film was made by the same team that made RBG including directors Julie Cohen and Betsy West, producer Talleah Bridges McMahon and editor Cinque Northern. My conversation with Raschke, via email, began with that team.

Digital Cinema Report: Before we get started, congratulations on your work on RBG. That is one of the best and most entertaining documentaries I’ve ever seen and, if I had anything to say about it, you would have won the Oscar for it. The same team that did that film made My Name is Pauli Murray. What advantages are there to working with the same people on different films?

Claudia Raschke: There are many advantages of working with the same creative team on a new project. One can rely on a trusting relationship and understand how to complement each other on set. Also, the level of professionalism and respect made our teamwork seamless while facing the pandemic and having to adjust to very strict COVID rules during principal photography. There is definitely a richer communication about setting a visual tone, and more opportunities for developing creative ideas as far as capturing the modern-day scenes. But I think our shared passion to make meaningful films about equal rights activists made us partner up for the documentary My Name Is Pauli Murray.

DCR: I haven’t seen the movie yet, but the trailer suggests that there was a lot of archival material available. How much of a voice did you have in deciding what to use? I ask that because it strikes me that those decisions have an impact on the look of the film.

DCR: I haven’t seen the movie yet, but the trailer suggests that there was a lot of archival material available. How much of a voice did you have in deciding what to use? I ask that because it strikes me that those decisions have an impact on the look of the film.

CR: The film leaned heavily on archival footage to tell the story of Pauli Murray, an African American civil rights activist, who was arrested for refusing to move to the back of the bus in Petersburg, Virginia 15 years before Rosa Parks; and Pauli organized restaurant sit-ins in Washington, D.C. 20 years before the Greensboro sit-ins. But the low resolution, partially damaged and rare archival video footage was going to be a challenge.

As the cinematographer I have no input which archival footage will be used. The directors Julie Cohen and Betsy West, our producer Talleah Bridges McMahon and our editor Cinque Northern make the decisions based on what was ultimately available and fitting for the story. So, for me the questions became how to integrate the modern-day footage, interviews and small cinema verité scenes, with the archival to create a visual framework that will be compelling and unifying. Not knowing which archival footage will be used and when or where the modern-day footage would be intercut made it clear that I had to create an overall naturalistic look for the interviews that could easily fit in anywhere while still setting an intimate tone.

DCR: Backing up for a second, did you have an idea in your head prior to starting about what the look of this film would be or is that something that develops for you over the course of shooting?

CR: There is a level of uncertainty during the process of making a documentary that will directly impact the cinematic approach. For example, some locations fell into place magically while others were hard to find and popped up in the very last minute. When you walk into an unknown situation it is key to embrace the location and make the best of it. To develop a cinematic look based on the unpredictable made me think about similarities locations might offer. I thought that maybe by selecting certain compositional elements, adding lighting finesse, and a painterly depth of field, it might create the right unifying framework for the interviews. I chose a naturalistic lighting approach and incorporated a spacious background with windows for each interview whenever possible. The idea was to set up one large source as if sunlight was filtering in through the windows. I applied this idea to each particular location with either existing or imagined windows and treated the background by setting up highlights the way sunlight can accentuate hidden details in a room, giving it a sense of character and depth. For me it solidified this idea of being at someone’s home connecting the viewer to a personal story with a reoccurring background layer of windows to the past, present, and future.

CR: There is a level of uncertainty during the process of making a documentary that will directly impact the cinematic approach. For example, some locations fell into place magically while others were hard to find and popped up in the very last minute. When you walk into an unknown situation it is key to embrace the location and make the best of it. To develop a cinematic look based on the unpredictable made me think about similarities locations might offer. I thought that maybe by selecting certain compositional elements, adding lighting finesse, and a painterly depth of field, it might create the right unifying framework for the interviews. I chose a naturalistic lighting approach and incorporated a spacious background with windows for each interview whenever possible. The idea was to set up one large source as if sunlight was filtering in through the windows. I applied this idea to each particular location with either existing or imagined windows and treated the background by setting up highlights the way sunlight can accentuate hidden details in a room, giving it a sense of character and depth. For me it solidified this idea of being at someone’s home connecting the viewer to a personal story with a reoccurring background layer of windows to the past, present, and future.

DCR: What camera or cameras did you shoot with on this film and what factors were involved in that decision? Do you have a go-to-camera or does each project dictate that choice?

CR: It is most effective when the DP chooses the best tools for a project. For this film all the interviews were shot with two cameras, the Canon C300 mark ii with Canon cinema primes. They were a fantastic combination to create beautiful images, glowing skin tones and capture a large dynamic range with deep shadow details and exquisite highlights. Canon’s sensor technology allows me to be an artist; I can pull out all the stops for my desired look. This is especially important when I need to adjust to challenging documentary scenes in low lights or with extreme contrast. Without the sensor’s latitude and easy to modify camera settings I wouldn’t be able to instantaneously capture and react to unpredictable cinema verité moments. It is important to remain nimble and reactive with a camera rig to seize the moment gracefully. The Canon C300 mark ii is one of my top choices for documentary filmmaking.

DCR: Similar question regarding lens choices?

DCR: Similar question regarding lens choices?

CR: Having the right optics is incredibly important to successfully capture the story. Our interview set-ups were mostly shot with a combination of a 50mm and 85mm or a 50mm and the 135mm Canon cinema primes with an aperture setting of T2.2 to provide a painterly shallow depth of field. These primes are sharp, fast and very reliable in every situation.

During the cinema verité moments I switched to the 18-80mm Canon compact zoom and also used my favorite 17-120mm Canon cine zoom. It is an excellent cine zoom lens that allows me to capture beautiful landscape shots and the ability to push in spontaneously for revealing close ups. Intercutting the Canon primes with the Canon cine zoom is seamless and makes them my go to lens choice.

DCR: Documentaries invariably face challenges and surprises, especially during the shoot. Sometimes they can be happy surprises. What did you run into on this film?

CR: The biggest challenge for a mostly archival driven film is really the color correction process. One has to balance the different archival source materials with the prepared graphics and the modern-day footage. Thankfully, shooting at 4K in LOG with cinema gamut settings allowed me lots of space to adjust. At times we added grain while other times we pushed the contrast levels of the modern footage to create a better match with the archival. At times washed out archival footage could not be altered because it would have given it an even more damaged look. It’s hard to know what I have to work with until we sit in the online color correct session to navigate the various archival images. It is amazing to see how far the digital sensor technology has come in comparison to the old archival video recordings we used in My Name Is Pauli Murray.

DCR: Best of luck at Sundance.

CR: Thank you!